Skawennati, TimeTraveller™, 2008-2013, HD machinima video (Courtesy the artist and Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon)

HACKING / MODDING / REMIXING as Feminist Protest

Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon

5000 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA

On view until February 26, 2017

Even as feminism experiences a resurgence, there’s still a marked lack of representation of women of color and gender nonconforming individuals in both art and political activism. This disparity was recently debated on an international level with the criticism launched at the disproportionately white and cisgender Women’s March. A current show HACKING / MODDING / REMIXING As Feminist Protest at Pittsburgh’s Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon provides a direct rebuke of this continued inequality by emphasizing the power of intersectional feminism (feminism that embraces multiple, overlapping social identities beyond gender, including race, ethnicity, sexuality and class).

The exhibition leads by example by bringing together a group of twenty two artists who fracture and rearrange technology to create their own narratives within male-dominated fields like gaming, net developing and computing. Organized by artist and game developer Angela Washko, the show, in many ways, is an answer to the much-reported lack of women in tech industries (Washko cites a 2013 study in her introductory wall text, stating only 26% of the positions in computing jobs in the U.S. are held by women). But, with its smart and diverse curation, HACKING / MODDING / REMIXING As Feminist Protest goes further than exhibitions about feminism often go, taking on race and other identity issues. This makes the show not only politically relevant, but also necessary viewing during our current feminist revival.

The show, though, doesn’t get off to a good start. In a corner of the entrance, a small plastic table covered in Barbie memorabilia and assorted toys greets viewers like a children’s play area. A Nintendo system on the table features Rachel Simone Weil’s Hello Kitty Land, a hacked version of Super Mario Bros. that replaces Mario with Hello Kitty and other Sanrio characters. By switching masculine plumber Mario with saccharine Hello Kitty, Weil’s raises girlish femininity to the heroic roles typically reserved for men. At first, it’s adorable, but, after more consideration, it’s kind of dumb.

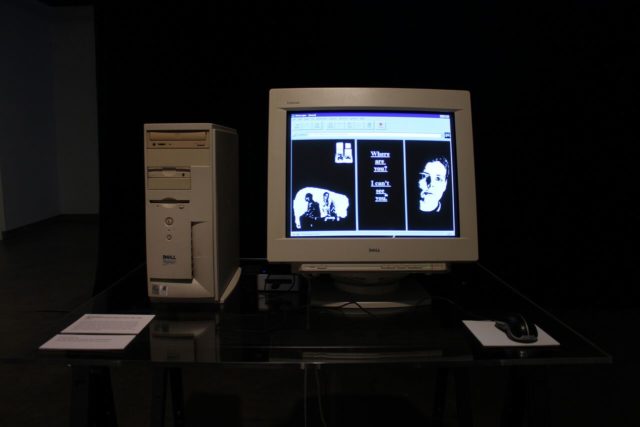

Installation view of Olia Lialina’s My Boyfriend Came Back From The War in Hacking / Modding / Remixing as Feminist Protest exhibition at the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, 2017

Luckily, the rest of the show, which filled all three floors of the Miller Gallery, abandoned this cutesy feminist cliché for a more complex and expansive range of work. The show presents such a wide range of technology that it almost looks like a tech showroom. Some of these inclusions are pretty retro including an old desktop computer, displaying Olia Lialina’s early click-based poetry My Boyfriend Came Back From The War and Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Laserdisc Lorna, described here as the first interactive video art disk. While not overtly political (though it could be argued that, with the underrepresentation of women in tech, just working with technology as a woman artist is a feminist act), these works act as historical precedents to the more biting commentary by younger artists.

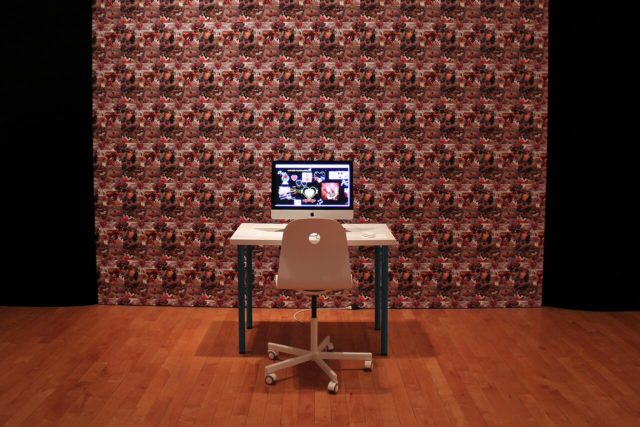

Beyond a loose genealogy of digital feminist interventions, Washko showcases a diversity of political and cultural concerns beyond just the views of white, cisgender women artists. While this should be the typical job of a curator, a show that refuses to resort to single identity-driven choices while embracing a cacophony of critiques feels fresh. These critiques range from the legacy of First Nations and Aboriginal histories in Skawennati’s feature length Second Life film TimeTraveller™ to police violence in Sondra Perry’s netherrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr 1.0.2, which combines Microsoft Windows’ blue screen of death with the blue shield of police-enforced silence on the wrongful deaths of black women. Other works deal with trans identity and gender fluidity including micha cárdenas’ Becoming Dragon, which documents the artist’s 365 hours living as a dragon in Second Life. This performance questions the year of “real life experience” transgender individuals must fulfill before qualifying for Gender Confirmation Surgery.

micha cárdenas, Becoming Dragon, 2008. digital prints, digital video (Courtesy the artists and Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon)

While many of these works are successful individually, some were even more engaging together. Iranian American artist Morehshin Allahyari’s net art Like Pearls and RAFiA Santana’s Black Power Project, which both use the over-the-top aesthetics of GIFs. Allahyari’s Like Pearls looks like a spam folder gone rogue. Overlaid with a grating electronic version of The Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way,” Allahyari’s work is full of flashing and blingee-d GIFs of hearts, butterflies and roses. Between the GIFs, advertisements of women hock lingerie with their bodies whited out, a reference to Iran’s censorship of these images. When viewers click on one of the GIFs, they’re directed to another page, which features an erotic yet slightly threatening statement. One GIF leads viewers to the phrase: “Give her the gift she can’t refuse.” Through Like Pearls, Allahyari reveals the dual desire and danger that comes from living under a regime that heavily polices women’s bodies and sexuality.

Installation view of Morehshin Allahyari’s Like Pearls in HACKING/MODDING/REMIXING as Feminist Protest exhibition at the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, 2017 (Courtesy the artist and Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon)

Nearby, RAFiA Santana’s Black Power Project also employs the exaggerated, seizure-inducing quality of GIFs. But here, the GIFs address white musicians and celebrities’ obsession with black fashion and culture. In one GIF, Macklemore, wearing a crown, stands in front of a raised, closed fist, symbolizing black power. Suddenly, he turns black, as do Iggy Azalea and Kylie Jenner in subsequent GIF projections. By pushing these pop stars’ appropriation of black symbols and fashion to its absolute, offensive limit–blackface, Santana’s collection of GIFs, despite their cheery colors, reminds viewers that cultural appropriation can be its own form of violence.

While taken independently, I’m not sure I would have even enjoyed RAFiA Santana GIFs, but viewed with Like Pearls, these two GIF-based works portray how marginalized identities can manipulate kitschy and glitchy form of digital technology to pointedly critique oppression. While each take aim at different issues–censorship in Iran and the cooptation of black culture, both artists reveal a parallel rejection of patriarchal power and white supremacy.

Similar conversations between included works occur again and again throughout the exhibition. By making space for multiple identities in HACKING / MODDING / REMIXING As Feminist Protest, Washko shows how disparate and diverse voices strengthen, rather than take away from, active forms of resistance. And at a time when intersectional feminism is rarely successfully achieved either in art or political activism, the show presents a much-needed refresher of how formidable it can be.

Comments on this entry are closed.