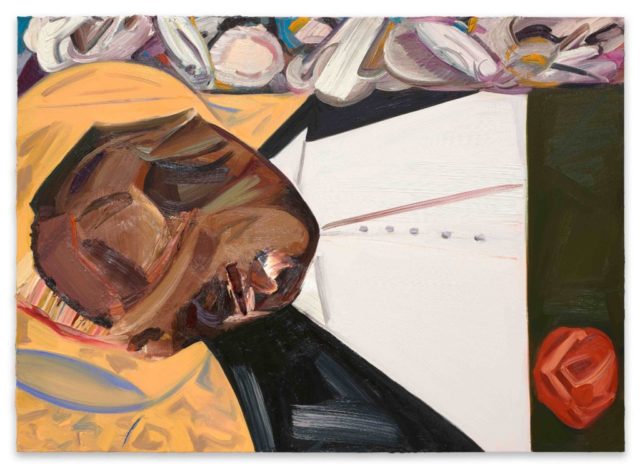

Dana Schutz, Open Casket (2016). Oil on canvas. Collection of the artist; courtesy Petzel, New York.

Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, the blogz—if you can type on the platform and you’re in the art world, you’ve probably weighed in on the debate over Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till. The painting is based on a photograph of African American Emmett Till, laid in a coffin. The 14 year old young man was brutally murdered in 1955 for flirting with a white woman, his face horrifically disfigured in process. Earlier this year, it came out that the accuser, Carolyn Bryant, had lied and made the story up.

The painting in question is a marvel to look at and currently on view at the Whitney Biennial. Schutz layers and builds paint in such a way that it appears economical even though she’s literally built a swollen lip out of paint. Schutz is a white artist, though, and many find the rendering of a black corpse with its face slashed (and aestheticized) insensitive.

Artist and writer Legacy Russell eloquently expressed a problem with Schutz’s use of abstraction over Facebook, arguing that to abstract a figure that was originally used for political purpose is the equivalent of closing the coffin. This problem is only augmented by the audiences museums tend to serve—white, elite and institutional. Hrag Vartanian, at Hyperallergic, believes Schutz had a responsibility to insert her own insights rather than treat the subject formally and obscure the subject matter. Meanwhile, Hannah Black, who wrote a letter of protest calling for the painting’s destruction, finds the reality that Schutz could sell the painting problematic. “It’s not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun,” she writes.

Many of the critiques above hold merit. It’s absolutely true that the figure is unrecognizable, which lends credence to the argument that the painting doesn’t pay proper respect to its subject. It is a masterfully painted, yet imperfect painting.

Other arguments feel less convincing. For example, I’m not sure I believe a moral imperative needs to be the driving force behind a decision to make a painting like this, as Vartanian seems to suggest in his piece. It should be enough to re-present history so it can be looked at afresh—we don’t need to rewrite it every time.

This might be considered a quibble, though, compared to some of the more extreme arguments I’ve seen on social media and expressed in Black’s call for removal. Currently circulating on Facebook is the idea that white people shouldn’t participate at all in the discussion because they aren’t directly affected. As a member of the arts community, and a white critic, I disagree. I believe stronger communities are built through an equal representation of all voices. That’s not going to happen if we start dictating who should and shouldn’t get to speak.

Another idea that initially troubled me is Hannah Black’s proposition that Schutz has no right to treat black pain as raw material. While I recognize that the artist hasn’t shared this experience, the belief that suffering can and should be owned goes nowhere good because it precludes (or at least makes very difficult) the possibility of both empathy and sympathy. Without compassion all discourse breaks down.

The trouble, though, is that when this painting is sold shown [Update: The artist has said she does not plan on selling the painting] a slew of white people (the artist, dealer, museum) will profit off the spectacle of Black suffering. In response to that particular issue, one astute commenter explained to me earlier today on Facebook that she thought, “some artistic freedom should be given up on the part of white artists in acknowledgement of the ways in which Black artists are still not free to ‘objectively’ represent their own bodies and history.”

Prior to that conversation, if you’d asked me if I thought it was a good idea for white artists to refrain from rendering certain racially charged subjects, I would have responded with a rant about how all this debate would lead only to white artists depicting black subjects less frequently. I’m not sure that position would have been wrong, but I’d now add the caveat that some subjects might be worth leaving alone. I write this knowing this road has “slippery slope” written all over it. After all, I’ve now written about this painting. Am I now profiting off black suffering too? I don’t think so, but then again it’s in my interest to think that.

Whatever the case, I love this painting and I’m glad I had the privilege of seeing it. But at the end of the day, I also have to acknowledge that it may not square with how much distress its caused.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }