“Atari Football” (1978) Photo credit: Thanassi Karageorgiou / Museum of the Moving Image.

Now that our culture has crossed the hurdle of recognizing that video games are more than just a time-wasting triviality that rots your brain, institutions have to grapple with how to preserve and present the rapidly forming canon. The Museum of the Moving Image in Queens was the first museum to collect video games and its currently showing off some prime gems in the exhibition, “Arcade Classics: Video Games from the Collection.” (on through October 23rd)

Art F City sat down with the museum’s Curator of Digital Media, Jason Eppink, to discuss the difficulties of preservation, how VR may become the new social medium and exactly why Duchamp was such a dedicated gamer.

Can you talk about the problems of preserving and displaying arcade games as a cultural artifact?

One thing that was really cool [about this exhibition] is that it gave us the opportunity to invest in a lot of preservation. There are few cultural products in museums that you are invited to interact with so a lot of these [machines] have wear and tear and have been in our storage space for a long time, not really functioning. We were able to redo everything; rebuild monitors and replace lots of parts that were faltering. And, actually, what we learned is that the preservationists in the past have not been as precise as we would normally like to be. So we were able to undo some [previous efforts] and bring them back up to more original standards.

As time goes on, the fragility and cultural value of a particular machine will grow, but if visitors aren’t allowed to play it, has it completely lost its original purpose? Should they always be allowed to play it and we just get comfortable with the fact that it will eventually be refurbished to the point of containing none of its original parts?

Yeah, there’s lots of things to talk about there. So, MoMA recently started collecting video games and they really have the long view on this. They’re working from the ground up. They’re getting the source code, they’re making sure it works on open source tools so that there are no copyright or trademark issues. They’re making sure that this emulation is gonna last for a long time. And it takes an institution of that size to have the resources to do that. They’re focused on ‘how do we present this to an audience with the long view?’ While I have some criticisms of what they’re doing, I think there’s a specific perspective they have, that’s really smart.

Our perspective on game preservation is that the game is the entire material experience. If that’s an arcade game that means that it’s the full artifact; it’s the cabinet, the joysticks, the CRT monitor etc. But, like you say, that’s not a hundred year vision. We acknowledge that and our perspective is making these artifacts available to an audience for as long as possible in their original form.

You’re obviously cataloging what you restore and replace. What happens when there’s nothing original left?

Yeah, I mean if all our cells are replaced are we the same person as before? I think that it’s a sort of deep philosophical question that a lot of preservationists lose sleep over. At some points, you just have to be practical. You have to ask yourself is the arcade game its individual parts, is it the sum of its parts?

“Galaxy Force II” (1988) Photo credit: Thanassi Karageorgiou / Museum of the Moving Image.

Well, for instance, the cabinet and the cabinet art that’s on it. Is that something that you touch up or is that maybe, where you draw the line and say we’ll just let it degrade?

It’s case-by-case. It’s hard to explain a larger rule there. Game historians have benefitted from private collectors who have the capital, and the time frankly, to devote to building this really amazing community. And their own micro-economy where people will reproduce cabinet art and panels that aren’t technically original but are so close that the community sort of agrees that it’s equal to a replacement. So, we benefit a lot from those sorts of things coming out. In some cases, we will replace a visual/aesthetic element with a reproduction. And if you think about most cultural artifacts that is, in many cases, anathema.

I honestly think that cabinet art is one of the least interesting aspects of an arcade machine. Because it was on the side, it often didn’t define your initial encounter with it. If it even did at all, often cabinets were so close together that you couldn’t even see the sides. I think marquees are a little more interesting and worth a little more handwringing. But that’s just a personal thing.

I think the most interesting part of the cabinet art was that it wasn’t usually very representative of what you’re about to do.

Absolutely. That was the place where publishers got to spark your imagination for what these small sprites actually were, or represented. Space Invaders is a really good one because there’s this sort of stenciled monster on the side which has nothing to do with looking down at these … creatures with right angles that are coming at you.

When we first talked about doing this interview you said that you would have “less to say about games as art and more about the nuance of games as a cultural product.” What did you mean by that?

If we have to categorize things into art and not art, I certainly think that there are video games that can fall into the category of art. No questions asked. But I think that’s a really narrow way to look at the world. A more interesting way to look at the world is to understand, all these things, art and not art, that are aesthetic experiences as culture, as cultural products. We get away from the, ‘is it art or not’ question, which I think is largely unproductive and it allows us to talk more about how it reflects our society, our values, our technological considerations. I think it puts aside some of the troubles of video games as primarily a business. I think that one way people define art is that there’s some sort of scarcity to it and there’s just no way that most of the games that we encounter could be made inside that kind of economic model. If we can dispose of having to apologize for the economics, then I think we can look at what’s interesting about video games.

Just to clarify, you’re saying that maybe if we worry about visual culture more than ART, we get a better idea of what a cultural institution’s mission might be?

Absolutely. We’re not an art museum. I describe it as ‘we fall somewhere in between an art museum, history museum and science museum.’ Those are the three major types and we sort of have our feet in all of those. So, again, video games are cultural products. Some would argue, and I agree with them, that they define our present moment the most as a cultural product. It’s important if we’re telling the story of material history to preserve those things and present them to an audience.

One of the specific things about this show is that there is really an opportunity to get a peek at what games would become. You get a chance to encounter those first moments and get a sense of what their impact was on video games.

When a classic video game is playable online, what value does it have in a physical space? What value does a physical, cultural institution’s presentation of the game bring to it?

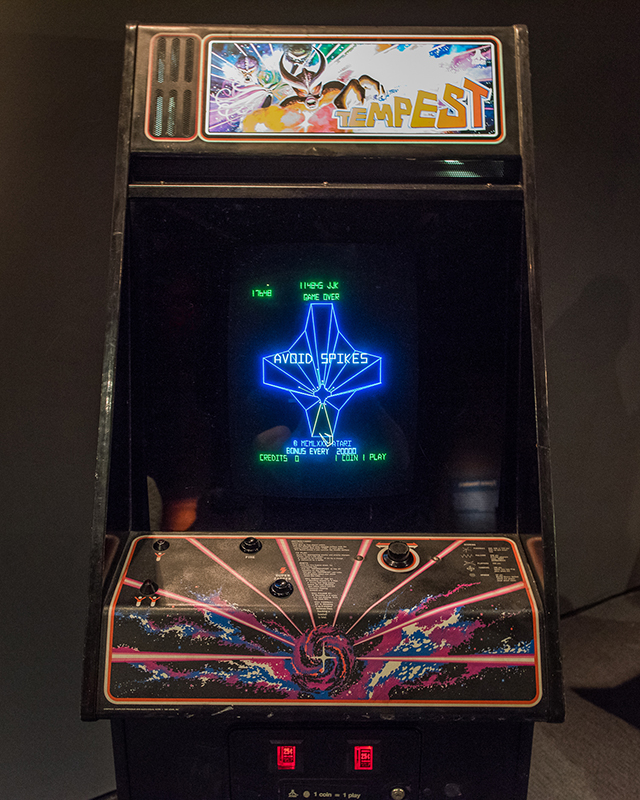

I should have a logline. It should be a simple answer but it never is. I think it sort of goes back to the difference between what MoMA’s doing and what we’re doing. The game experience is the complete encounter with the original artifact. Everything from how the button press feels, how spaced out the controls are. The CRT monitor is really important, LCD displays are very, very different from CRT’s. Especially vector monitors, which Asteroids, Tempest, Star Wars and Battlezone are on. They look very different. Also, I think it’s important to encounter them in social spaces. Some would argue that it’s important to exhibit them in an arcade-like atmosphere and I think there’s some value in that. But I also think there’s some value in decontextualizing them a bit.

TEMPEST (1981) Photo credit: Thanassi Karageorgiou / Museum of the Moving Image

In Korea, gaming cafes are a huge enterprise and function as a mainstream social space. This seems like a logical progression of the function that arcades used to serve. Why do you think this sort of social space hasn’t really caught on in America and other countries?

I think, partly, that’s just sort of the American story. As soon as we can put it in our homes we do. It’s sort of the story of the suburbs. As a culture, I think we’ve always valued owning privately if we can. Like with a washing machine. There are practical considerations but also we just prefer to do it in the comfort of our own homes.

In the early 2000’s you had the promise of network gaming. So, gaming became social but online. Now, there seems to be a growing interest in “local multiplayer games.” Games that you play together in physical space. I’m really seeing that a lot in the indie space, almost exclusively the games that I’m excited about are young designers who are like, “actually games are something I like to play in my dorm room with friends.” It becomes a party. Sports Friends is a great example.

Certainly, we don’t have arcades like we did before. It always comes back to economics. Arcade games are expensive to make and technological turnaround is so fast that maybe it doesn’t make sense to invest in a multi-thousand-dollar object that’s going to be outdated in six months.

Relatedly, ya know, everyone is sooo excited about VR. The one hope I think VR has is that cinemas are starting to carve out spaces where they’ll have some VR headsets. You’ll come to a theater, you pay a price and encounter this VR experience. So you don’t have to own the damn thing. That takes away the hardware costs and makes it a social experience. Even though you’re strapped in, afterward you’re with your friends and other people and you talk about what you just experienced.

So you think the next step in how games and technological advancement will be social is by putting people in a room and isolating them more?

[Laughs] Yeah I do. Is having a headset on really that much more isolating than being engrossed in a game of Pac-Man? I don’t know. I think we’re talking about degrees here. I think we have a visual bias when there’s not too much of a difference. That’s my guess.

I was recently at Kickstarter’s headquarters and they had one of the largest and most beautiful arcade cabinets I’ve seen. One of their employees told me that it was a Kickstarter-funded project. Do you think the age of arcade games has already come and gone? Will there be another wave of people creating these objects in the way that vinyl has re-appeared or will it be more of an anachronism like a unicycle?

Babycastles has a great program where they have a set of arcades that are neutral and they can fit anything. They’re thinking very much about how to put these games in social spaces. Death By Audio arcades is another example. Also, Barcade is doing well, they’re expanding and are very popular.

Missile Command (1980) Photo credit: Daniel Love / Museum of the Moving Image

You’re saying that there’s a big opportunity for arcades to exist but without these dedicated cabinets?

Yeah, there are more games in the world than we’ll ever be able to play in our lifetimes and there’s not a lot of reason to let one take up ten square feet or whatever. But also the practicality of a cabinet is that these things can’t get up and walk off. Playing on a laptop or an iPad has these exhibition challenges. That’s a real argument for arcades. You can put [cabinets] in a space and safely play them.

Duchamp loved games, he famously loved chess, and I find it interesting that he said chess, “has all the beauty of art—and much more. It cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position.” I think the commercial viability of games is something that stands as a barrier to them being taken seriously. But lately, because the tools for making games have become easier to use or more accessible, you have these auteurs making some pretty uncommercial work that is being taken seriously. Do you think that critical and institutional respect gravitates towards the work that is most vulnerable and in need of support?

It’s funny. My understanding of when something becomes art, in the capital-A art world is when it does start making money for people.

It’s interesting that Duchamp uses Chess as an example because the joy of Chess is not in its aesthetics. Just to use Duchamp as a jumping off-point, Frank Lantz, who is the director of the Game Center at NYU, is the one who finally gave me a metaphor about why we enjoy games. He uses the word aesthetics in the Kantian sense which means, a thing that we engage in for pleasure that is not utilitarian. He compares different cultural products or art with our senses. As humans, we spend most of our day looking at things for utilitarian purposes; using our vision. But a painting or visual art is about taking pleasure in looking.

What Frank says, is that games are about the pleasure of engaging in systems. Every day, in our lives, we’re interacting inside political systems or bureaucracies or social systems. We walk down the street on a grid and we sort of negotiate all the rules that we have in place. So with games, it’s about existing inside that system, understanding its intricacies and subtleties and learning how to take advantage of, play inside of and exploit that system to achieve a goal. I think that we have natural aversion tools but there’s actually a lot of pleasure that can come from existing inside a set of rules.

So, my read on that quote is that Duchamp is finding pleasure in existing inside that system. Of thinking through a very elegant system that evolved over centuries.

The other reason I bring that up is that I think emphasis from the fine art/visual art world is sort of on the visual aesthetics of games. Which are not to be ignored, but I think [that emphasis] leaves out the more interesting parts of games.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }