Farley Aguilar, Boy School, 2016, Oil on linen (Courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York)

Farley Aguilar: Bad Color Book

Lyles & King

106 Forsyth Street

New York, NY

On view until February 12, 2017

Sometimes it takes the right sociopolitical moment for an artist’s work to land its critique. That’s precisely what happened with Farley Aguilar’s paintings, currently on view in his solo show Bad Color Book at Lyles & King.

A couple years ago when I saw his work at Volta New York, I wrote off the Florida-based artist’s monumental splattered canvases as a throwback to the hypermasculine, “bigger is better” style of painting. But, his current exhibition, filled with threatening representations of crowds, resonates with the populist anger and frenzied mob mentality tapped into by Donald Trump. While Aguilar sourced his painting’s imagery from vintage photographs, his themes, rendered with an anxious, frenetic hand, are chillingly timely.

Farley Aguilar, Boy With Two Rabbits, 2016, Oil on linen (Courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York)

There’s no easing into this show. After descending the gallery’s stairs, Aguilar’s life-size Boy With Two Rabbits hangs immediately to the left of the shelf covered with press releases and checklists. The painting stands as if looking over the viewers’ shoulders. With two red-rimmed eyes, matching his knit cap, the boy looks like a zombie. And holding two dead rabbits in his hands, outlined in thick black and orange lines of paint, the painting provides a jarring introduction to the show.

Beyond Boy With Two Rabbits’s thousand-yard stare, the rest of the show features six enormous canvases by the self-taught painter. Aguilar’s strange combination of anachronistic, clothing styles, hallucinatory color schemes and ambiguous scenes initially feel out of time and place, even when the source materials are old photographs. And yet, what feels distinctly contemporary is the works’ frantic and fearful energy. This is achieved through Aguilar’s jagged, electrifying lines and uncanny representation of faces with blank or spiraled eyes and crossed-out mouths. With countless hollow-eyed faces gazing from the canvases, the exhibition provides a nerve-wracking viewing experience, reminiscent of Rashid Johnson’s Anxious Men paintings.

Farley Aguilar, Mother and Child, 2016, Oil on linen (Courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York)

Certain works grotesquely distort the idyllic scenes from his source materials, which allows for a deeper understanding of Aguilar’s political critique. Take, for example, Mother and Child, which depicts a woman sewing a star on an American flag with her blonde child. The painting resembles a photograph by May Smith, published in 1917 by National Geographic. In Smith’s photograph, the sewing scene is tender and idealistic, portraying a mother’s careful stitching while her daughter watches with impish curiosity. The photo is a sweet portrait of both family and nation coming together.

Conversely, in Aguilar’s hands, this patriotic dream becomes a nightmare. With the child’s gaping holes for eyes and the infinity circle scrawled on the mother’s forehead, both mother and child appear possessed. They sit on a black couch in front of almost bare, cement-colored walls. It looks like a bunker rather than a warm and welcoming living room. In contrast to an adorable image of old-timey American pride, it’s scary–much like patriotism today, which, as seen in the 2016 presidential election, can easily translate into violent hate crimes. Here, patriotism becomes a form of mind control and can be harnessed for nefarious means.

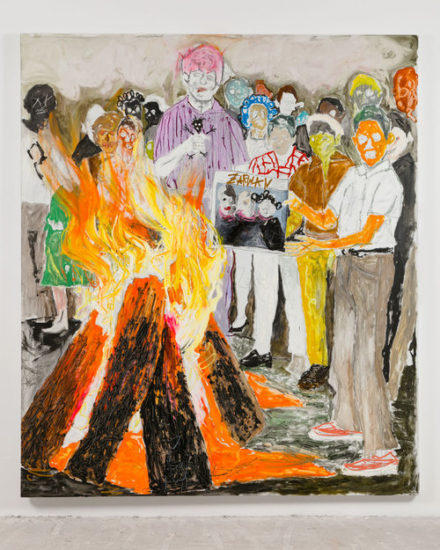

Farley Aguilar, The Burning, 2016, Oil on linen (Courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York)

Aguilar most successfully renders the threat of populism in his paintings of large, ominous crowds. For instance, in his painting The Burning, he portrays a mob standing behind a giant bonfire. In the foreground, a boy proudly holds an album, which vaguely resembles The Beatles’ Meet The Beatles. With some selective Googling, I found the source image for this painting–a photograph of the 1966 burning of The Beatles albums in the American South after John Lennon said the band was “more popular than Jesus.”

Drawing on the darkness of the original photograph, The Burning transforms this image into an equally creepy but less precise and perhaps even more frightening representation of mob mentality. The bodies of the numerous figures blur together, only revealing the haunting jack-o’-lantern faces of the crowd. The central figure, holding a tiny figurine that looks like a voodoo doll, is the most realistically rendered, even with pink hair and bright white skin. The thickly painted and vivid flames leap up menacingly, pointing to an underlying potential of violence. With no legible emotional expression or distinctive time and place, this sinister crowd could be anywhere in the United States.

Farley Aguilar, Women in Line, 2016, Oil on linen (Courtesy the artist and Lyles & King, New York)

Not all of Aguilar’s critique, though, is lobbed at rural Americans. For example, Women In Line presents a more urban scene with ten women and one child waiting politely in single file in front of a backward American flag. Wearing short dresses and, in one case, nothing, the women seem less threatening than their rural counterparts. But, several forward-facing figures maintain the unsettling visages seen in his other works. One woman’s face is smeared with exaggerated red lips and rings of purple and black around her eyes. Behind her, the child’s barely discernible, blank features look like an outtake from Children of the Corn. Rather than a possibly deadly mob scene like The Burning, Women In Line portrays a drone-like vacancy. And when combined with the gigantic American flag behind them, the painting becomes a biting response to American passivity.

Oddly enough, that may be the one element of the show that doesn’t directly relate to our current political system. Today, the American people seem anything but passive. Instead, they are willing to wage war against anyone they perceive as interfering with their well-being. While it’s hard to understand why a sizable portion of the country has a seemingly limitless devotion to a leader working against their interests, perhaps the most prescient and haunting message of Aguilar’s paintings is that they are, in fact, all of us.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }