Robyn O’Neil, Inflation Drill (after Guston), 2016, Graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery)

Robyn O’Neil: The Good Herd

Susan Inglett Gallery

522 West 24th Street

New York, NY

On view until March 11, 2017

Is any art that depicts a vivid sense of doom and gloom immediately relevant in 2017? Yes, if Robyn O’Neil’s current solo exhibition The Good Herd is any indication.

Previously, the Los Angeles-based artist’s dark surrealism felt like an anachronism. Her drawings in exhibitions like 2011’s Hell were, at once, a throwback to Odilon Redon’s trippy drawings and Edward Gorey’s Goth wit. This didn’t exactly click during the comparative calm of the Obama years. But now, with the daily hellish roller coaster of Trump’s administration, O’Neil’s anonymous figures and ominous symbolism have become strikingly timely, addressing the isolation many feel from their fellow Americans who voted an orange demagogue into office.

The gallery divides the show into two rooms, mostly based on size, with her monumental graphite drawings in the larger central gallery and a handful of smaller works in the back. While a practical logistical decision, this organization works in the shows favor because it gathers all of O’Neil’s deeply creepy crowd drawings into the exhibition’s front room. This makes for a startling introduction.

Robyn O’Neil, Studies In Suffocation I, 2016, graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery)

Faceless, bowed heads peek through rolling waves and jagged cliffs on nearly every wall of the front room. All the viewer can see are the tops of the subjects’ hair and occasionally, their ears. With precise draftsmanship, the works could be mistaken for collage with the figures’ heads folded into the landscape. There’s also a certain sameness to all the works. But instead of feeling mundane, this heightened the sense of being surrounded by copious amounts of people. Individually, drawings like Studies of Suffocation I and II are claustrophobic. But, seen together, the works are an agoraphobic’s worst fear.

Granted, the frantic anxiety and instability of groups isn’t a new topic in contemporary art. But, rather than zeroing in on one frenzied individual in a sea of bodies like Alex Prager’s photographs or a collective insanity like Farley Aguilar’s paintings, O’Neil’s figures seem to exist independently from one another. With their heads turned down in varying directions, it looks like each figure is praying or staring at their smartphone. These crowds consist of a multitude of isolated individuals.

Robyn O’Neil, Government Bureau (After Tooker), 2016, graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery)

This successful depiction of public alienation becomes a more pointed sociopolitical critique when read in the context of the art historical references O’Neil places in her work titles. Take, for example, Government Bureau (After Tooker), which features a man and a woman turned from one another with their faces blocked by an ambiguous mountain range. The title refers to George Tooker’s 1956 painting, which represents a bureaucratic nightmare at the New York City Building Department. The workers in Tooker’s painting, in contrast to O’Neil’s figures, are all eyes, peering out from peepholes behind desks at the drone-like line of visitors.

While Tooker’s piece highlights the government-sanctioned distance between employees and patrons, O’Neil’s Government Bureau (After Tooker) portrays the physical division between two individuals that are inches apart. This isn’t to say their separation isn’t also governmentally motivated. The drawing seems to point to our current political state, in which both sides of the political spectrum refuse to listen to each other. And because of this, the piece couldn’t feel more spot-on.

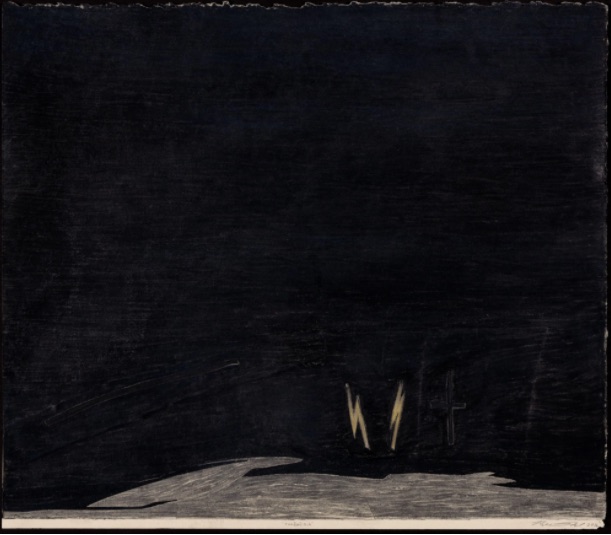

Robyn O’Neil, Threnoidia, 2016, graphite and prisma on paper (Courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery)

This compelling sense of isolation falters in the second gallery where O’Neil places her smaller, bleak landscapes. Some of these landscapes are downright spooky as seen in These Moments, which portrays nine silhouettes of masculine faces against a sky of mountain peaks. But, it wasn’t enough to hold my interest. These works, as a whole, don’t have the critical edge and affective impact of her large-scale crowd drawings.

There was, however, one standout: her shadowy Threnoidia. The piece features a deep, black background that is shades darker than the rest of the exhibition. In the drawing’s foreground, the artist carves two bright lightening bolts into the darkness. Beside these sudden zigzags, she faintly renders a cross. It feels unsettling like an abandoned gravesite.

Upon closer inspection, even though I’m not entirely sure this was O’Neil’s intent, the two white zigzags eerily resemble the Nazi SS symbol. When analyzed with the cross standing parallel to these two signs, the drawing seems like a visual representation of the notorious and chilling quote, attributed to Sinclair Lewis (though it’s origins are contested), about fascism coming to America “wrapped in a flag and carrying a cross.” And with the drawing’s title derived from the Greek word for a mourning hymn or poem, Threnoidia feels like a memorial to both our present and future society.

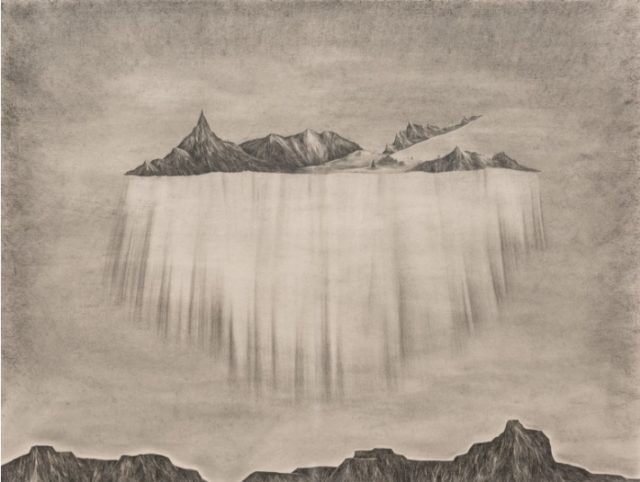

Robyn O’Neil, Ascension, 2016, graphite on paper (Courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery)

Thankfully, before I left The Good Herd completely depressed, I spotted a glimmer of light within the seemingly unending darkness of the exhibition. This hope came from the drawing Ascension, which depicts a tract of land floating up toward the sky like it’s being raptured, separated from the rocky hills below. Granted, it’s a little Left Behind, but it also seems to point to the promise of escape. This moment of relief was much appreciated, indicating that even in the darkest shows the possibility of transcendence remains.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }