We need to talk…, Installation view, Petzel, 2017 (Courtesy of the artists and Petzel, New York)

We Need To Talk…

Petzel Gallery

456 West 18th Street

New York, NY

On view until February 11, 2017

Since Trump’s election, numerous exhibitions have attempted to address the seemingly endless horror of his presidency. But, how should we judge these shows’ efficacy? Is the quality of the included work enough or should viewers demand more practical political action? A visit to Petzel Gallery’s disappointing We Need To Talk… convinced me of the latter.

The exhibition’s proposed exploration of the many fraught issues currently under siege seemed promising. But, with an unwavering devotion to showing big name artists, half-assed attempts at engaging the general public and a convoluted donation strategy (the press release vaguely states, “A percentage of sales will be donated to any organization that seems appropriate to artist and collector.”), We Need To Talk… came out well short of its activist goals. So short, in fact, that the goals of the show itself were put into question.

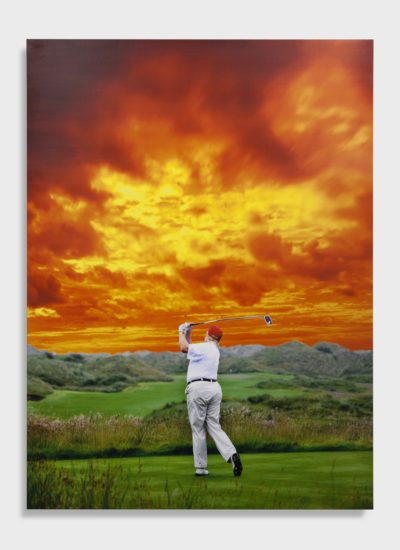

Like most recent exhibits launched in response to Trump, We Need To Talk… features plentiful representations of the President. His countenance lurks throughout the show like an orange-tinted boogieman. In fact, viewers can’t even enter the gallery without nearly tripping over his image. A stack of posters by Jonathan Horowitz sits on the floor just inside the doors. The posters depict Trump golfing during the apocalypse and are emblazoned with the quote, “Does she have a good body. No. Does she have a fat ass? Absolutely.” Not only is this foreboding, but it also encourages contemplation of Trump’s own round ass. Yuck.

Jonathan Horowitz, Does she have a good body? No. Does she have a fat ass? Absolutely., 2016, Digital C-print mounted on recycled hexacomb paperboard (Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London)

Even though I have a major case of Trump art burnout, I came to begrudgingly appreciate these Trump portraits. If it weren’t for these works, it would be almost impossible to tell the show was meant to reflect our political state. Various interpretations of the American flag by Robert Longo, AA Bronson and Hans Haacke hang in various states of disrepair, text-based works from Sarah Morris and Barbara Kruger shout “Liar” and “Who will write the history of tears?” and a neon by Yael Bartana asks, “What if women ruled the world?” Most of the inclusions were so generic, that they left little reason to talk about them after the fact, short of mentioning them with derision.

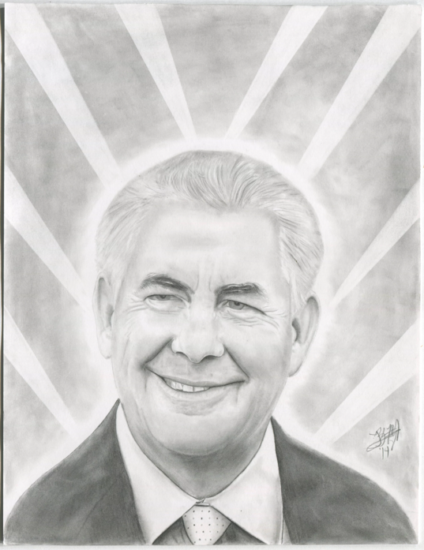

The most successful works, unsurprisingly, present a pointed engagement with sociopolitical issues. Take, for example, Andrew Ider and Jeff Greenspan’s The Captured Project (People in Prison Drawing People Who Should Be). Covering one freestanding wall, this series consists of portraits of CEOs of major companies such as Walmart, Goldman Sachs, Mosanto and Koch Industries. What pushes these works beyond straightforward representations is that they are all completed by people who are currently incarcerated. Amidst all the tiresome work by well-known artists in the gallery, it was refreshing to see art by individuals normally rendered silent and invisible.

Portrait of Rex Tillerson by Brandon Meyer, part of The Captured Project (image courtesy the artist and The Captured Project)

Not only does The Captured Project reveal the artistic talent of those currently in prison (which mirrors the recent success of On the Inside at Abrons Art Center), but it also blatantly depicts the unfairness of the American justice system. Beside the portraits is a similar grid of texts listing each individual CEO’s “crimes” including bribes, looting the public, theft and fraud and treason, as well as a listing the artists’ sentences for felonies like possession of a firearm and bank robbery. Reading these wall texts, it becomes unmistakably clear that these billionaires operate above the law. The installation becomes even more chilling once viewers notice that future Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is included, expanding the work’s already effective critique to a dire commentary on our corrupt political system.

As compelling as The Captured Project is, though, it’s not enough to fix the gallery’s awkward attempts at engaging the public. For instance, to the left of the entrance, the gallery presents a low round table featuring two open notebooks. Here, the gallery encourages viewers to write down their “reactions, thoughts, anxieties, hopes for the future.” But between the squat table, a container of pens and unlined notebooks, it felt more like a setup to encourage children to color. And this childishness was reflected in the public’s responses to the prompt. The first page I turned to was scrawled with “FUCK TRUMP” across an entire page. This wasn’t exactly the nuanced emotional outpouring of the Subway Therapy Project. Instead, it felt like graffiti scrawled on the walls of a dive bar bathroom.

We need to talk…, Installation view, Petzel, 2017 (Courtesy of the artists and Petzel, New York)

Then, there’s the issue of the press release’s reference to an unclear percentage of sales going to unnamed and undecided organizations. This left me scratching my head. Surely, some structured giving is needed to incentivize actual donations. I asked the gallery’s Publications Manager Janine Latham to clarify. She said, “At the moment the donation is entirely up to the artist, some artists wish to donate their entire share, others a percentage. The gallery will match the percentage that the artist donates…”

This didn’t do much to quell my skepticism over the tangible, measurable effect of the exhibition. Will the gallery produce a press release announcing the dollar amount they raised? Will they announce specifically who they donated to? Was there even a specific goal in mind other than nebulous do-goodery? Perhaps its weakness would have been less noticeable if not for the strength of recent grassroots-led exhibitions like the Knockdown Center’s Nasty Women, which closed with $42,500 raised for Planned Parenthood by art purchases of $100 or less. Whereas Nasty Women was a tactical and determined rebuke of a misogynist president, the philanthropic goals and political critique of We Need To Talk… felt like a feeble gesture in comparison. And in our dangerous political times, good intentions aren’t enough.

Comments on this entry are closed.