Brian Lotti, “The Great Outdoors”. Collection of Nicola Knight.

Wednesday 6/21

I am on a plane, wondering how it is possible that I have never been to Los Angeles before. I’m trying to synthesize all the conflicting reports I have received over the years about what to expect. Looking out the window, it strikes me that the only truth is that L.A. is unknowably vast.

The sprawl is a morphology utterly unlike the East Coast megalopolis—with its familiar semilinear logic of defined centers and hub-and-spoke suburbs. L.A. instead resembles an endless circuit board poured into the topography. The way the components relate to one another is a mystery—an endless grid of houses, oil derricks, highrises, strip malls, office parks, improbably massive warehouses, and meandering freeways repeating without any discernable pattern or hierarchy. Somewhere in the anonymous mix I know there are countless galleries, studios, and private collections. L.A. feels like a treasure hunt. I have never driven a car in my life. I’m intimidated.

On the phone at LAX, my friend is aghast at my plan to take the train from the airport and make my way to Hollywood via transfers to the subway. She insists I allow her to call me an Uber. Over the course of the over-an-hour-long ride through traffic the driver repeatedly mutters that he regrets accepting the fare. We’re both white-knuckled as we make our way up a series of narrow, winding roads in the Hollywood Hills, where houses cling to cliffs on stilts.

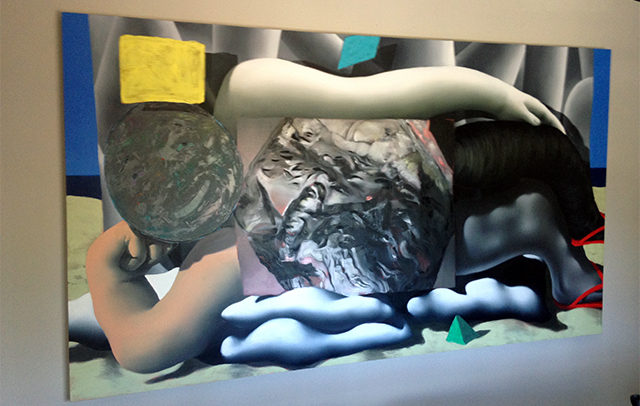

Jordan Kasey, “Shapes Person on the Beach,” 61.5″ x 108″, 2016. Collection of Nicola Knight.

I am staying with Nicola Knight, an art advisor, and her home is a testament to her niche skills in the trade—the walls are hung with a mix of work by professional contacts and emerging painter friends from our days back in Baltimore. It’s all the kind of art I would buy, visually striking with a sense of tension. In a stairwell, I’m seduced by the bright colors of a washy Brian Lotti L.A. streetscape. Staring at the big painting in the small space from below, it takes me a minute to realize the festive palette is owed to the colorful tents of a homeless encampment in the foreground. She has countless smaller works from D’Metrius John Rice, a large abstract painting by Seth Adelsberger, and dozens of works from other artists I hadn’t known. In her dining room, a reclining figure by Jordan Kasey sprawls across a canvas nearly as long as the table, her face a muddy smiley-emoji mask. Looking at the larger works, I imagine art handlers attempting to navigate a clumsy truck up the precarious mountain road and get a flash of mild panic.

Later, we’re sitting in another collector’s modernist home a few hills over. The few non-glass walls are tightly-packed with paintings and photographs, with others still wrapped leaning against them, obscuring what’s underneath. There’s a Nick Cave sound suit casually hanging out in the corner. While I’m trying to identify the works through the pile and packing materials, a woman looks at my worn and patched jeans and asks, “So did you used to be an actual punk rocker or something?”

I pretend I didn’t hear her and instead gesture to the wall, “Wow, it seems like everyone in L.A. has such a great collection!” As soon as I say this I realize how dumb it sounds. I have only been in two homes in the few hours I’ve been in town.

“Yes, it’s true!” she replies.

Friday 6/23

Conor Fields, “Tide Pool” (center) with Isabell Yellin, “Hug me, Hold me, Don’t Let Me Go” (left).

We show up customarily last-minute to an opening at Skibum MacArthur, a gallery in a hangar-like building of artist studios known as Tin Flats. The group show, Detour West curated by Lourença Alencar, feels appropriate to the industrial setting (nestled out-of-the-way between a highway and the concrete ditch of the L.A. River) and the provisional, at times surreal, landscape of the city at large. A Conor Fields installation, “Tide Pool”, is impossible to miss entering the space. Murky black liquid is pumped between a barrel and a cinderblock basin—a sinister tar pit mirrored by Isabell Yellin’s large, droopy leatherette and acrylic works.

Stephen Neidich, “Al Pastor” (foreground) with Andrea Marie Breiling, “In and Out”.

The mechanical whirring of Stephen Neidich’s assemblage “Al Pastor” echoes throughout the space. It’s a clanking rotisserie of industrial detritus. It’s oddly hypnotic, and I almost overlook three small drawings on Tyvek in the corner, also by Conor Fields. They delicately depict signifiers of suburbia—”googie” billboards and rolling hills—in green pointillism evocative of grass lawns. Or perhaps, given the material, astroturf. I think of those creaky oil derricks looming behind golf courses and McMansions. Los Angeles is far stranger and more worn than I had anticipated, and this show gets at the endearing awkwardness of its contradictions.

The sole exhibition text comprises this passage, nearly each word footnoted to a strange piece of local trivia or short poem:

“I live in Los Angeles and I’ve had seven heart attacks, all imagined. That is to say, I was deeply unhappy but I didn’t know it because I was so happy all the time. I have a favorite quote about LA by William Shakespeare. He said: ‘This other Eden, demi-paradise, this precious stone set in the silver sea, this earth, this realm, this Los Angeles’. Anyway, this is what happened to me. And I swear it’s all true.”

Including the footnote:

“Oil and water: naturally occurring substances that are both essential to the life of Angelinos. One is life giving and an essential element and the other is burned at a careless rate on an hourly basis. The five artists at Tin Flats—Andrea Marie Breiling, Conor Fields, Chandler McWilliams, Stephen Neidich, and Isabel Yellin—came to LA, this land of oil and water, from elsewhere, each with their own dreams, loves, and baggage.”

A friend drives us to a friend-of-a-friend’s going-away party on the roof of a pre-war highrise downtown. Nearly everyone is also from somewhere else (our hostess, a chemist, is moving back to Berlin). A group of these transplants happen to be art writers as well. They have just come from the opening of Los Angeles’ new tallest building—an affair accompanied by commissioned artworks ranging from site-specific installations and ice sculptures to Korean opera, performance art, and lasers. They say it was all terrible. Looking out over the newly-crowned smoggy skyline, I get my first glimpse of L.A. that looks like Blade Runner.

Saturday, 6/24

I have been told it’s a long wait for an appointment to see the Marciano Arts Foundation, a new private museum funded by the GUESS? Jeans fortune. Miraculously, I manage to score two last-minute tickets. We arrive 45 minutes late for our time spot thanks to traffic, but the staff seem to have expected that. The museum is housed in an old Masonic lodge from 1961 that looks vaguely like a kitschier version of a Nazi office building, and the bizarre and storied context informs a lot of the work that’s been acquired for the inaugural show, curated by Philipp Kaiser.

The exhibition is a triumph—and one that never seems to take itself too seriously at that.

Installation View: Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, “

Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch, for example, approached the Marcianos in 2014 and proposed a residency within the vacant structure for several months before renovations began. The end product is a multi-channel video installation installed in a tent that harkens to the apparent “slumber party” vibe of the residency—when a rotating cast of drag queens and art weirdos ran wild through the cultish bunker of a space. The piece recalls some of Trecartin’s best work (even Zoe the documentarian character from “A Family Finds Entertainment” makes an appearance.) It’s fun and punk and delightfully unpolished. At one point the mischief-makers throw caterpillar-like rows of chairs from the balcony of the theater (which once sat 2,000 people. Sadly, the city forced the foundation to remove the auditorium because they couldn’t provide enough parking to accommodate audiences that large, despite the fact that there’s a multibillion-dollar subway line being constructed under the avenue outside). I’m reminded of the anarchic theater-squatters in John Waters’ Cecil B. DeMented, and the installation reads like an invitation to join in their rebellious sleep-over.

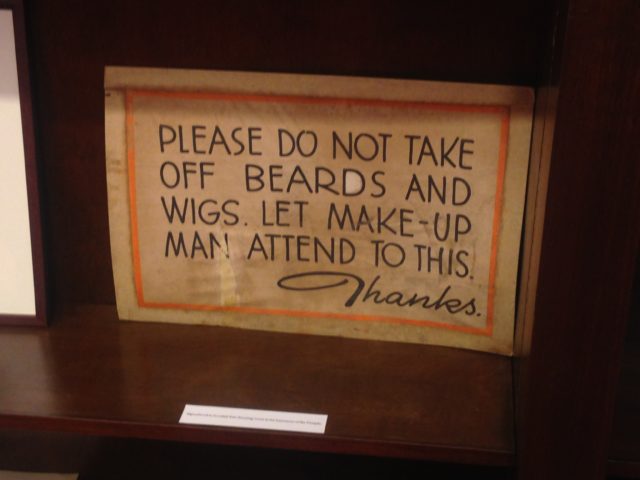

The Masons also left behind a treasure trove of props and sets from their theatrical religious/political rituals (some of which are on display in a small gallery off the mezzanine, such as the above sign). Others have been incorporated into a massive, immersive apocalyptic installation by Jim Shaw, The Wig Museum, alongside original works by the artist from both the Marciano Collection and his own (more about this, and the permanent collection, later). Some works in the collection coincidentally feel site-specific, such as a massive wall piece from 2010 in which Cindy Sherman dons ritualistic garb, which was offered to the foundation a few years later, after they bought their equally esoteric bunker of a building.

Surpassing all expectations, The Marciano Foundation ends up being one of the best art-viewing experiences I’ve had in recent memory. For a private museum focused on one collection, the exhibitions feel playful and surprisingly artist-centric. I’m told the Marciano brothers have opened the space to artists to experiment and respond to, and in several instances end up acquiring the results. It’s a strategy that’s worked well.

Alex Israel, “Valet Parking,” 2013/2017. Oil Ppainting on wall.

Most of the works on view are exemplary of each artist in the collection’s best practices. A series of trompe-l’œil oil paint murals by Alex Israel wrap around the mezzanine of the lobby, and it’s probably my favorite work I’ve seen by the artist. The piece, “Valet Parking”, recreates elements of an L.A. streetscape (parking meters and signs, sandwich boards advertising tours, street trees, etc…) without buildings or people. Nearly every component feels lovingly resolved, and appropriately like an update of the Mason’s hand-painted theatrical backdrops.

One chamber of Jim Shaw’s haunted-house like installation “The Wig Museum”, incorporating apocalyptic set pieces left behind by the Masons alongside original works, such as his anarchist strip mall backdrop and cutout figures.

I think of the show I’d seen the night before, and how much the idiosyncrasies of Los Angeles end up being the subject of exhibitions or conversation here. There’s a certain snobbery I’ve encountered where non-Angelenos describe the city as a suburban “non-place”, and it’s reassuring to see artists and curators celebrating all the things that make L.A. singularly off-beat—from the vibe of a post-apocalyptic “American Dream” to hulking mid-century ruins left by secret societies. I find myself suddenly tempted to join a cult.

Sunday 6/25

That’s Hogwarts Castle, as seen at Universal Studios from the Hollywood Hills. I’ve been calling it “Smogwarts”.

I share another impossibly long Uber ride to Venice Beach with a local artist. He tells me that he’s frustrated because he never gets shows—collectors buy directly from studio visits, but he hasn’t exhibited through a gallery in years. I think that’s not such a bad problem to have, as far as problems go.

Monday 6/26

I decide to venture out on foot. My Google walking directions lead me down a sidewalk that dead-ends with a crosswalk to a highway median. Never have I felt more like the hapless tourist Simone De Beauvoir described in “America Day by Day”, when she attempted to cross the West Side Highway to reach the Hudson River on her first visit to New York City. I’m equally embarrassed and afraid I’m going to die.

I think of Reyner Banham (author of ” Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies”,) and his famous quote, “like earlier generations of English intellectuals who taught themselves Italian in order to read Dante in the original, I learned to drive to read Los Angeles in the original.” I, on the other hand, am too stubborn to call an Uber and press on into my own circle of hell.

A harrowing 45 minutes later I’m in the more pedestrian-scaled streets of Hollywood. Fully embracing this hapless tourist persona, I use Yelp to look up “art galleries” and “museums” within walking distance that are open on Mondays. The closest is the Psychiatry: An Industry of Death Museum, which promises multiple exhibits (with video) and is run by the dubious-sounding “Citizen’s Commission on Human Rights.” The other is the Museum of Broken Relationships Los Angeles.

L.A. (and in particular, Hollywood) is weird as fuck. And maybe, just a little lonely.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 6 trackbacks }