Thomas Tilly, Charlotte Moorman performs Aria 4 of Nam June Paik’s Opera Sextronique, Düsseldorf, West Germany, October 7, 1968, Courtesy AFORK (Archiv künstlerischer Fotografie der rheinischen Kunstszene), Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf

Despite the misogynistic horror of Donald Trump’s campaign and eventual election victory, 2016 was a great year for women in the art. There were compelling solo exhibitions by women artists in major institutions, a copious list of all-women group shows and dynamic revivals of unfairly overlooked female artists’ careers. It seems like 2016 marked the return of much-needed 1990’s-style “girl power.”

Granted, there’s still a long way to go for equal representation, particularly for women artists of color. But, hopefully, this is just the beginning. To celebrate this year’s exciting and timely return to feminism, I selected the ten best shows featuring women in 2016. Results below:

1)Marilyn Minter: Pretty/Dirty at the Brooklyn Museum

Marilyn Minter, “Pop Rocks”, 2009, enamel on metal (Collection of Danielle and David Ganek; Courtesy the Brooklyn Museum)

Paddy reviewed this expansive retrospective back in 2015 at Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, but it’s so timely that I feel confident including the Brooklyn Museum’s incarnation on this list. Part of the museum’s A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism, Minter’s Pretty/Dirty presents feminism in the form of unabashedly raunchy female eroticism. The entire retrospective is a sensual playground of sucking mouths, steamy glass, sweaty glitter and oozing sticking fluids. Simply put, it’s hot.

Beyond Minter’s well-known saliva-drenched paintings like “Pop Rocks,” the exhibition also showcases some of the artist’s early work like her photographic series Coral Ridge Towers. These photographs portray the artist’s reclusive mother as she primps in opulent mirrors like Sunset Boulevard’s faded star Norma Desmond. While a stark contrast to her later color-drenched series, these black-and-white photographs powerfully trace a personal story behind Minter’s career-long fascination with glamour, feminine beauty and excess.

2) Carolee Schneemann: Further Evidence–Exhibit A and B at PPOW Gallery and Galerie Lelong

Carolee Schneemann, Fresh Blood, 1983/2004, c-print (© Carolee Schneemann; Courtesy PPOW Gallery; Photo: James Brown)

Some exhibitions by women this year became more poignant in the context of Donald Trump’s election and the fear of his resulting administration’s crackdown on women’s rights. Feminist stalwart Carolee Schneemann’s dual exhibitions at PPOW Gallery and Galerie Lelong were two of these shows. Delving into Schneemann’s lesser-known works, Further Evidence–Exhibit A and Further Evidence–Exhibit B were difficult and disturbing. Rotting oranges punctured with hypodermic needles, multi-channel videos featuring dancing prisoners and collages of caged cats don’t exactly scream accessibility. But, unsettling viewers came with a purpose. As I wrote in my review, Schneemann’s depiction of the female body as “contested, controlled and imprisoned” resonated in our dangerous sociopolitical moment.

3) Simone Leigh: The Waiting Room at the New Museum

Simone Leigh in The Waiting Room (Photo: Kevin Hagen for The Wall Street Journal)

As many in the art world look for a way forward in the age of Trump, I keep returning to Simone Leigh’s The Waiting Room as an example of what an effective combination of art and activism might look like. Leigh’s fifth floor installation drew on the history of local herbalists and wellness centers opened in the black community (predominantly by black women) as a means to address gaps in an inadequate, inaccessible and uncaring health care system. The strength of The Waiting Room wasn’t its aesthetic—which resembled a combination of an apothecary with rows of jars filled with indeterminate herbs and a new age-y yoga studio with pillows strewn on the floor. Instead, Leigh powerfully organized a series of community-focused public programs for healing and solidarity, which included massages, acupuncture and meditation. In particular, the event Black Women Artists For Black Lives Matter showed how self-care and collectivity could be a form of political resistance.

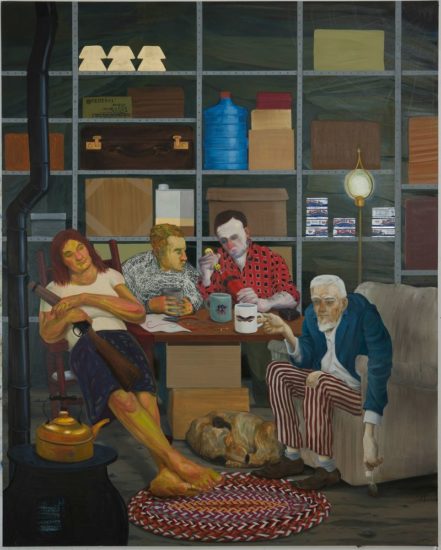

4) Nicole Eisenman: Al-ugh-ories at the New Museum

Nicole Eisenman, Tea Party, 2011, oil on canvas (Courtesy the artist and the New Museum)

The New Museum also featured a number of career-spanning solo exhibitions by women artists this year including Pipilotti Rist’s current Pixel Forest. For me, though, the standout was Nicole Eisenman’s mid-career survey Al-ugh-ories, which almost exclusively focused on her painting practice. It’s not easy to make paintings funny, art historically focused and politically relevant, but Eisenman succeeds. In particular, her painting “Tea Party,” which depicts a dissolute Uncle Sam making a bomb with his fellow bunker colleagues, seems particularly apt in the era of the alt-right.

Even more than the content of the paintings themselves, what made the show so significant was how actively excited Eisenman’s art made viewers. I visited the show on one of the Museum’s packed Thursday nights and I still remember watching numerous viewers pause, consider and discuss the paintings. It’s rare you see that level of enthusiasm for such a traditional medium, which speaks to the depth and necessity of Eisenman’s work.

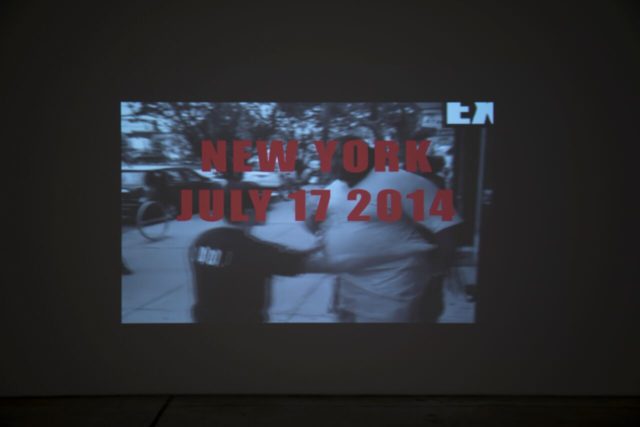

5) Carrie Mae Weems at Jack Shainman Gallery

Installation view of Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys: Video in Three Parts, 2016 (©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

Jack Shainman’s two concurrent Carrie Mae Weems’ exhibitions juxtapose the increased representation of blackness in mainstream television with the violence against black bodies. While the show at Jack Shainman’s 21st Street space presented a more conventional gathering of Weems’ art, including her new series Scenes & Take, her exhibition at the 24th Street gallery on the killings of unarmed black men by police was so gut-wrenching it’s hard to forget. From her photographs of men in hoodies with a red bar over their faces to emotionless bureaucratic death reports, Weems puts institutionalized racism front and center for a privileged Chelsea-going art audience. In particular, her video All The Boys: Video In Three Parts uses the real cell phone footage of the deaths of Eric Garner, Philandro Castile and others to transform viewers into active witnesses of these crimes, as I explored in my review.

6) Sondra Perry: Resident Evil at The Kitchen

Installation view of Sondra Perry’s Resident Evil at The Kitchen (Photo: Jason Mandella)

I caught Sondra Perry’s exhibition Resident Evil at the Kitchen right before it closed. And I’m so glad I did. Set against a viscous background of her own skin, the exhibition presented a multifaceted look at the surveillance and policing of black bodies through a combination of unusable exercise machines filled with hair gel, Microsoft’s blue screen of death, the artist’s own glitchy avatar and the dystopian narrative of the Alien franchise. The most stunning piece in the show was Resident Evil, which combined footage of the protests after Freddie Gray’s murder in Baltimore, ominously shaky film taken outside and in her home in New Jersey and Eartha Kitt’s “I Want To Be Evil.” More than just a critique of the perception of blackness as evil, Perry, particularly with her inclusion of Kitt’s purring performance, points to a subversive embrace of badness as a means to regain agency.

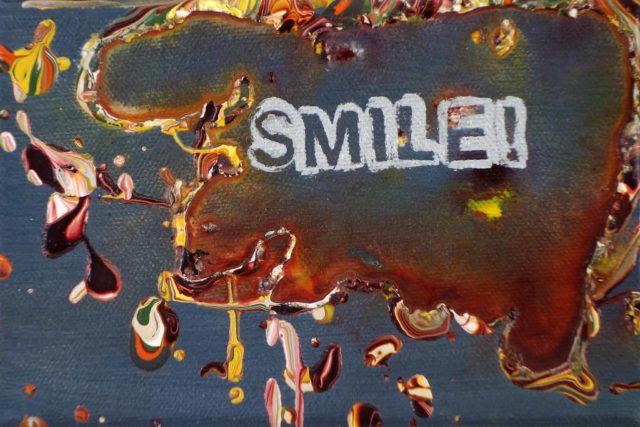

7) Smile! at Shin Gallery‘s Project Space

Betty Tompkins, “Smile!” 2016. Image courtesy Shin Gallery.

This summer brought a staggering influx of group exhibitions featuring only women artists. Of these, the standout was a small, unexpected project space show Smile! at Shin Gallery. Curated by Jenny Mushkin Goldman, the exhibition was organized in reference to Joe Scarborough’s tone deaf tweet to Hillary Clinton during the primaries, which read “Smile. You just had a big night.” While text-based works from Betty Tompkins and Deborah Kass directly referenced cat-calling, other pieces combatted the patriarchy through refreshingly off-the-wall depictions of femininity and female sexuality. Rebecca Goyette’s campy film Lobstapus/Lobstapussy asserted a thoroughly bizarre form of lobster claw-sporting hypersexuality while Hyon Gyon’s installation, featuring teapots covered in pearls, ribbons and cigarette butts, destroyed traditional notions of feminine objects. Overall, the show felt like a nuanced rebuke of female objectification through female creativity.

8) Charlotte Moorman: A Feast Of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde, 1960s-1980s at Grey Art Gallery

Hartmut Beifuss, Charlotte Moorman performing Nam June Paik’s TV Bed, Bochum Art Week, Bochum, West Germany, 1973, Digital print, Peter Wenzel Collection. © Hartmut Beifuss (all images courtesy the Grey Art Gallery)

2016 was the year I learned Charlotte Moorman was a badass. The fact that I never heard of her before is a testament to the continued misogyny of the art world. But, the Grey Art Gallery’s A Feast Of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde, 1960s-1980s did a good job of posthumously returning Moorman to her rightful place in the art history. The show asserted that Moorman was more than a passive mannequin in her collaborations with Fluxus greats like Nam June Paik, John Cage and Jim McWilliams. Known at the “Topless Cellist,” she not only made these original scores her own, but was a completely fearless performer. Through archival footage and even, some recorded interviews with Moorman, A Feast Of Astonishments presented Moorman playing the cello covered in chocolate, flying over an audience tied to balloons and, perhaps most notably, getting arrested for indecent exposure in a performance of Nam June Paik’s Opera Sextronique.

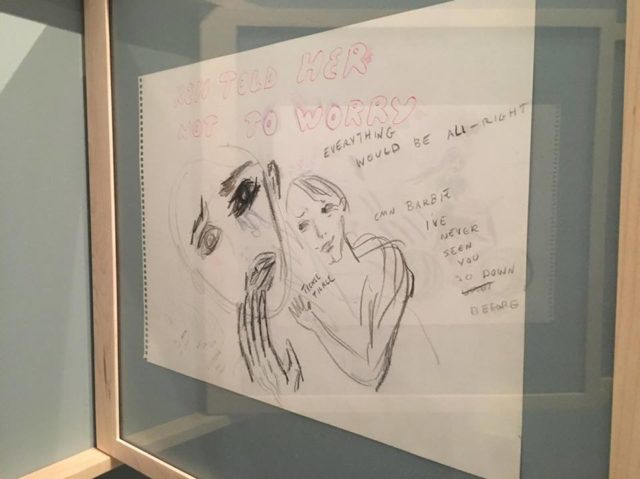

9) Ellen Cantor: Are You Ready For Love? at 80 Washington Square East Galleries

One of Ellen Cantor’s notebooks at Are You Ready For Love? (Photo by author)

This fall saw a multi-venue revival of Ellen Cantor’s prolific multidisciplinary work, which included shows at several galleries, a recreation of the Cantor’s group show Coming To Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-plicit Art By Woman at Maccarone and a screening of her final film Pinochet Porn at MoMA. Of these, though, the most captivating and comprehensive was 80 Washington Square East’s Are You Ready For Love? Beginning with her monumental drawings of Snow White as she finds love–or at least sex–in the enchanted forest, the show revealed Cantor’s career-long fascination with love. Cantor’s notion of love was not a whirlwind romantic fantasy out of a Nicholas Sparks novel. Instead, it was depicted here as obsessive, erotic, lustful, and sometimes violent—as seen most clearly in her numerous notebooks on display. With each individual page of these notebooks hung in movable frames, the viewing experience took on a tactile sensuousness that reflected the desire in the narratives between their covers.

10) Betty Tompkins: WOMEN Words, Phrases and Stories at FLAG Art Foundation

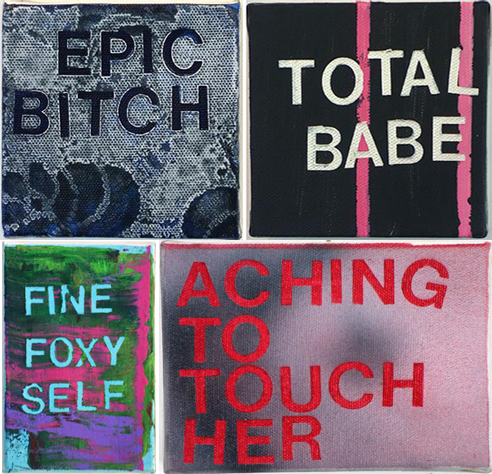

Four works in Betty Tompkins’ WOMEN Words, Phrases, and Stories (Courtesy the artist and FLAG Art Foundation)

It’s hard to forget the experience of viewing a painting that reads “Three Hole Wonder.” That momentary combination of shock and involuntary laughter is the strength of Betty Tompkins’s staggering series WOMEN Words, Phrases and Stories, exhibited in full at FLAG Art Foundation. With 1000 variously sized canvases hung salon-style on the walls, the installation was a jaw-dropping example of how women are defined linguistically. Tompkins crowd-sourced these phrases over email, admitting in the press release that she received over 3,500 responses. While some of the paintings featured obvious derogatory terms like “Bitch” or “Cunt,” others were sweet like “Honey” or downright bizarre like “You never know if you are going to get a fuck you or a chicken dinner.” These paintings, while admittedly funny, prove just how language is used to control women’s bodies, actions and sexuality. Not just a critique, though, the sheer scope of Tompkins’ series felt like a bold feminist reappropriation of these phrases.

Comments on this entry are closed.